I have no nostalgia for my childhood

Dear Reader,

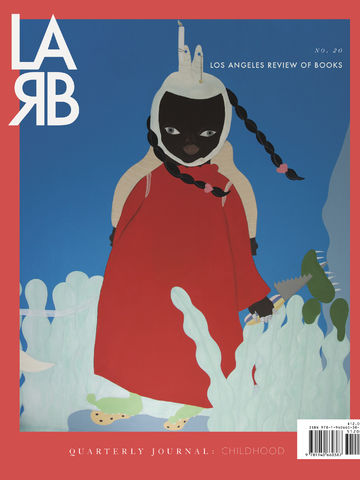

I have no nostalgia for my childhood. I don’t remember it well — maybe less than I should — and I don’t miss it or long for it. I am in fact, grateful it’s over, as I don’t recall it being particularly fun or easy. As far as I can tell, childhood is a pretty scary time, with little control over your life, little understanding of what’s happening and why, and much to be afraid of (both real and unreal terrors).

Dear Reader,

I have no nostalgia for my childhood. I don’t remember it well — maybe less than I should — and I don’t miss it or long for it. I am in fact, grateful it’s over, as I don’t recall it being particularly fun or easy. As far as I can tell, childhood is a pretty scary time, with little control over your life, little understanding of what’s happening and why, and much to be afraid of (both real and unreal terrors).

I have certainly met people who think of their childhoods fondly, describe them as “happy” even. Childhood is itself an odd thing, since it is both shared and so particularly ours. Think about the strangeness of the word — it can be both plural and singular, general and individual. Who else has the body memory of a little you? And yet, even memory might be a composite, reconstructed from the stories and memories of others. The news cycle also reminds us that childhood is a political reality — it has been under attack at the borders of this country for some time now. It is also a historical reality — childhoods change all the time. They have changed even within the past 10 years.

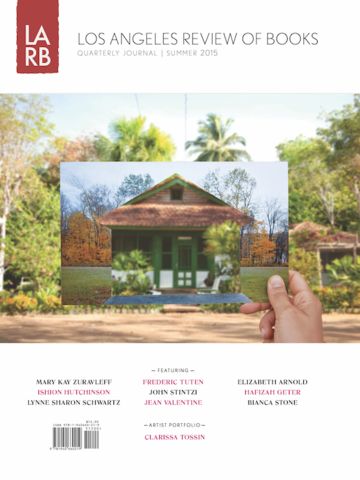

This issue of the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal explores these different ways of understanding what childhood is. Margaret Hagerman presents her research on how children learn about race and racism in our current political and historical moment. Edith Sheffer translates an entire file from the archives of the Third Reich, revealing how a child in the 1940s was diagnosed, classified, and placed. From a more personal perspective, Michelle Cruz Gonzales considers belonging to Indian Club in elementary school. Weike Wang writes about a mother debating which version of Cinderella to show her child. Katherine J. Chen thinks about her name and the impact it had on her throughout her life. E.C. Osondu’s short story deals with alien babies, and that horrible day when the space ship finally comes to pick them up.

This issue is not exactly for children, but for those who were children, which is to say, all of us. There are so many reasons to return to that time, whether we cherish it or think of it wearily, whether we really remember it or not.

Yours,

Medaya

ESSAYS

NOBODY HAS BLINDED ME by J.D. Daniels

SEEN AND HEARD: REMEMBERING CHILDREN’S ART AND ACTIVISM by Marah Gubar

THE GIRL IN THE FILE: MARGARETE SCHAFFER UNDER NAZI PSYCHIATRY by Edith Sheffer

MOTHER, FIRE by Shanthi Sekaran

THOSE WHO CARE AND THOSE WHO DON’T: CHILDREN AND RACISM IN THE ERA OF TRUMP by Margaret Hagerman

FICTION

THE CHANGED PARTY by Andrew Martin

HOW TO RAISE AN AILEN BABY by E.C. Osondu

THE NEW YEAR by Justine Champine

INDIAN CLUB by Michelle Cruz Gonzales

POETRY

TWO POEMS by Jos Charles

JELLY by Henri Cole

FEAR AND LOATHING (COMIN’ AND GOIN’) by Anaïs Duplan

MA’AM, AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY by Marilyn Chin

VULNERABLE NETTLE by Jennifer S. Cheng

TWO POEMS by Leila Chatti

TWO POEMS by Rae Armantrout

SHORTS

ELLA by Weike Wang

FUNERAL WEAR by Rigoberto González

TUTOR by Alexandra Chang

WHAT’S IN A NAME? by Katherine J. Chen

MURDER IN THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL by Snigdha Poonam